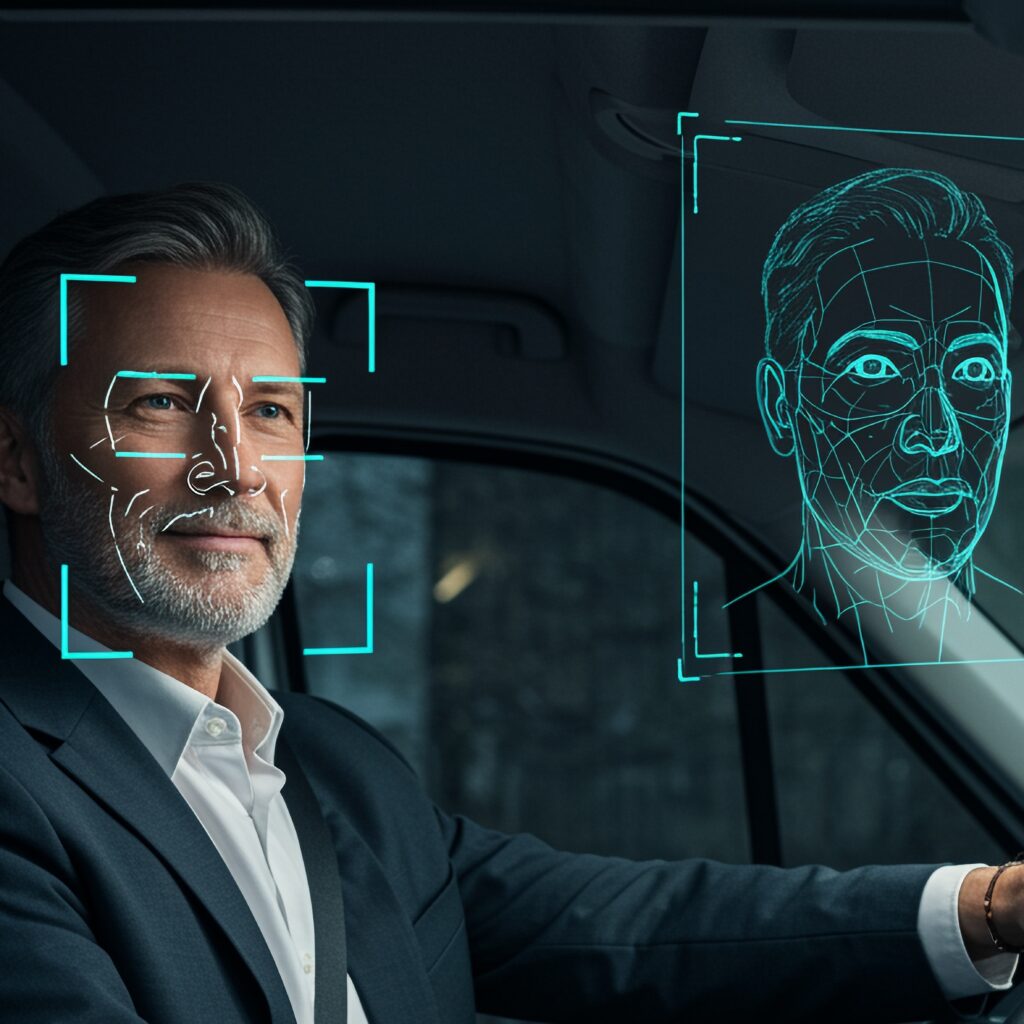

How to persuade drivers to accept in-vehicle cameras

For fleet managers, one of the most sensitive and challenging decisions they face is the implementation of in-vehicle camera systems in company vehicles. This is because the introduction of these cameras can often spark significant disagreement and debate among various stakeholders. Fleet managers must navigate potentially conflicting perspectives on topics such as privacy, safety, and productivity. Indeed, few topics create as much potential for friction as this single decision, making its resolution one of the most delicate tasks that a fleet manager has to address.

For the business, forward and driver-facing cameras are useful tools that can improve driver safety, reduce insurance costs, and defend accident claims.

But depending how sensitively these cameras are introduced, employees, unions and works councils can reject them as unacceptable invasions of privacy and symbols of a ‘Big Brother’ approach from mistrustful employers.

To avoid employees covering camera lenses with tape or sabotaging systems, fleets need a clear communication strategy that explains both why they are introducing the technology and details how any video footage will be used. This is not just smart HR, there are important data compliance issues to understand as well.

Employees not drivers

To gain a degree of objective perspective before taking the decision to install cameras, it is useful to understand that many of the drivers involved do not consider themselves as ‘drivers’, said Oliver Temple, Channel Sales Leader for EMEA and APAC at Lytx, at the CV Show. In their own eyes these employees are technicians, engineers, electricians, plumbers, construction workers, and so on, who simply happen to drive a light commercial vehicle for work, rather than professional drivers.

This was immediately apparent to Circet, the largest private sector fleet in Ireland, as it started to introduce inward and outward facing cameras to its 3,000 vehicles six years ago. Early discussions involved different trades unions, each one responsible for representing employees with different skillsets and roles.

“We brought in the union representatives so they could understand why we were doing this, and we didn’t have any pushback from any of them,” said Ray Verschoyle, head of transport compliance, Circet Ireland & UK.

“You have to be open and transparent from the very start, and clearly define the purpose and use of the technology in the driver’s policy and in the employee’s handbook.”

Protection, not spying

He likens the situation to a business having CCTV in its reception area – it’s not there to spy, it’s there to help and protect. Emphasising the important the company attaches to driver safety, and the investment it is making to enhance safety, is a powerful message to bring drivers on board.

Moreover, Circet’s experience with the the Lytx Surfsight video safety platform has cemented driver support. Video evidence has been used to defend employees from claims that they were using their phones while driving and to reject false accident claims.

“We told our drivers and unions that we would use this technology to exonerate them from wrongful claims,” said Verschoyle.

No audio and limited video

Circet does not capture audio from its cameras, and only a very small number of very senior staff have access to the footage. Fleet managers might smile at the idea that they have nothing better to do all day than watch video feeds from thousands of vehicles, but they have to address this concern among drivers and reassure them of the limited use of video.

In most instances, new AI and machine learning systems only store and transmit a few seconds of film from the moments before a collision.

Broader applications of driver-facing cameras, such as detecting fatigue or distraction (from phone use, eating and drinking), as well as seatbelt use, can be restricted to in-cab alerts that only the driver hears. Fleet managers can, however, set parameters that inform them if a driver triggers too many alerts.

Data privacy regulation

Fleet managers also have to be aware of a raft of regulations and directives that govern data collection and storage, advised Jonathan Armstrong, Partner at Punter Southall Law.

Employers have to comply with multiple overlapping laws, such as GDPR and its national variations, with the risk of significant financial penalties for non-compliance.

In some markets this can include the right of employees to deactivate cameras and telematics devices during private use outside working hours. Employers should only collect the minimum data necessary and keep it only for as long as required, said Armstrong, adding that fleets should generally avoid collecting real-time location data or continuous video.

“Connected vehicle technology is revolutionising transport, but it comes with real and rising privacy and compliance risks,” said Armstrong.

Fleets and organisations across the automotive ecosystem have to act decisively, he added, as class actions, regulatory scrutiny and consumer awareness grow.

“With the right controls, transparency, and accountability, compliance can be achieved without stifling innovation. But those who ignore the risks do so at their peril,” said Armstrong.